You might have heard the story about the three traders who decided to go into the business of trading sardines. The first trader bought a can of sardines for $5. He sold the same can of sardines to the second trader for $10, doubling his money. The second trader again doubled his money by selling the can of sardines to the third trader for $20. The third trader, knowing very well that he was overpaying for the sardines said to himself that “if the market for sardines crashed, at least I will be able to open the can of sardines and eat it”. The market did crash, and he opened the can to find that the sardines were rotten. He promptly went to the trader who had sold him the bad sardines and said “these sardines are no good!”, to which the second trader responded “of course they are no good for eating – they are trading sardines”!

Almost 10 trillion USD worth of the world’s government bond market is currently like these sardines. When a bond has negative yield, like a majority of the bond market in Germany and Japan today does, the bonds are being bought for trading, not for holding as investments, unless we undertake some financial alchemy to figuratively turn garbage to gold (and vice versa). When, and if yields rise, a ten year German Bund trading today at -0.25% nominal yield will almost certainly lose a good part of its principal, and for those who hold it to maturity, will also likely provide no income for their investment. In other words, unless the current holders of the bonds are able to trade them to someone else before they lose value, they will likely find that these bonds were neither a good long term investment nor a diversifier.

Now on to the financial alchemy that in the short run can potentially turn negative yields into positive yields. Readers know that due to interest rate parity, a currency with a lower interest rate trades at a higher exchange rate in the future. For instance, if we look at the exchange rate for the Euro vs. USD, the one-year implied forward exchange rate (which is very much tradable as a forward or as a swap), is about 3 cents per Euro higher than the spot exchange rate (Source: Bloomberg)

The implied forward exchange rates for any pair of currencies is determined by the spot exchange rate, the differential of the money market rates for that tenor and the cross-currency basis swap, which essentially measures the demand and supply mismatch for the two currencies. For the purpose of this discussion we don’t need to understand the details of the basis swap. The only thing that the reader needs to know is that if he buys a German Bund at a negative yield of -0.25%, and then if he hedges the currency risk by selling the Euro currency forward to convert the proceeds over the hedge horizon into dollars, he is selling the forward exchange rate at a higher price than the spot exchange rate, so the difference between the forward exchange rate and the spot exchange rate can be considered additional “yield” coming from the hedge.

This forward currency hedging generates about 3%, so when we add 3% to -0.25%, we now have a negatively yielding ten year German Bund yielding +2.75% for a US investor! Similarly, a 3 month German Bund yielding -0.50% is about 2.5% hedged yield, and a two year German Bund yielding -0.67% is equivalent to a 2.30% hedged yield. On the other hand, for a Euro based investor, the act of hedging the currency risk reduces the yield of a ten year maturity Treasury note to -0.83%! In other words it converts positive US dollar yields (for a US Dollar investor) to negative yields (for a Euro investor).

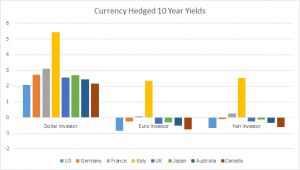

The chart below (Source: Morgan Stanley) shows the currency hedged yields of the US, Euro and Japanese 10 year maturity government bonds from the perspective of investors in various countries. Even though every country in this list has a much lower un-hedged yield than the US treasury (the lone exception is Italy, which I will come to below), the hedged yield for every country’s bonds is higher than the yield of the US 10 year Treasury. This is an example of the carry trade at its finest, and perhaps most dangerous. By taking a long term low yielding asset, and by using a derivative contract, the low yield is turned into a high yield, temporarily, and vice versa.

This state of affairs, where arguably the US 10 year treasury is lower hedged yield than any other country, is not completely an accident. Global Central Banks have been easing policy, while the US has been tightening policy – and this might soon begin to change.

The lower policy rates in foreign countries result in carry benefit in the “internal” market and also in the “external” market. For example, in Europe, very negative short term yields (-0.65%) result in positive carry even for a 10 year Bund at -0.25% for internal European buyers, such as indexers, or Euroland banks. This is because if one buys a bond at -0.25%, with a fixed yield curve shape the bond rolls down towards the more negative shorter term yield, which results in positive total return. Indeed, the increasing Target 2 deficits of Italy and others are a symptom of the fact that money is being recycled from Italy back into German Bunds, presumably because despite negative yields, the carry and safety of being in Bunds is worth the risks to Italian holders of Euros and Italian bonds. In addition, by reducing short term interest rates and the consequent application of the covered interest rate parity relationship, the Central Banks are unknowingly encouraging the kind of speculation we discussed previously, i.e. external buying of the negative yielding assets and converting them to positive yielding assets through the exchange rate.